|

|

Pain Control / Pain Management

|

Hypnotherapy notes

|

|

"Pain is an awareness created by the brain. Over time a strong memory of pain is created so future pain may be easier to feel because the message gets through more quickly. Hypnosis can help break that memory pattern."

Helen Crawford, associate professor of psychology at Virginia Tech.

More info

American Pain Society American Pain Society

Pain explained for kids Pain explained for kids

Hypnosis and pain Hypnosis and pain

|

|

Pain is a universal experience. The degree to which you feel pain and how you react to it, however, are the results of your own biological, psychological and cultural makeup. Past encounters with painful injury or illness also can influence your sensitivity to pain.

When pain persists beyond the time expected for an injury to heal or an illness to end, it can become a chronic condition. No longer is the pain viewed as just the symptom of another disease, but as an illness unto itself.

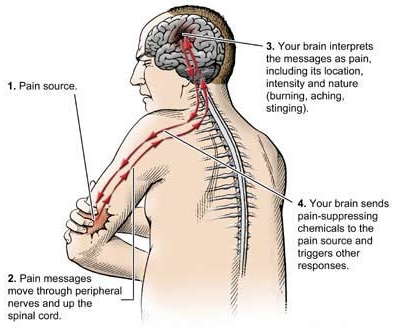

Pain basically results from a series of exchanges involving three major components: your peripheral nerves, spinal cord and brain.

Your peripheral nerves

Your peripheral nerves encompass a network of nerve fibers that branches throughout your body. Attached to some of these fibers are special nerve endings that can sense an unpleasant stimulus, such as a cut, burn or painful pressure. These nerve endings are called nociceptors.

You have millions of nociceptors in your skin, bones, joints and muscles and in the protective membrane around your internal organs. Nociceptors are concentrated in areas more prone to injury, such as your fingers and toes. That's why a splinter in your finger hurts more than one in your back or shoulder. There may be as many as 1,300 nociceptors in just 1 square inch of skin. Muscles, protected beneath your skin, have fewer nerve endings. And internal organs, protected by skin, muscle and bone, have fewer still.

Some nociceptors sense sharp blows, others heat. One type senses pressure, temperature and chemical changes. Nociceptors can also detect inflammation caused by injury, disease or infection.

When nociceptors detect a harmful stimulus, they relay their pain messages in the form of electrical impulses along a peripheral nerve to your spinal cord and brain. However, the speed by which the messages travel can vary. Sensations of severe pain are transmitted almost instantaneously. Dull, aching pain — such as an upset stomach or an earache — is relayed on fibers that transmit at a slower speed.

Your spinal cord

When pain messages reach your spinal cord, they meet up with specialized nerve cells that act as gatekeepers, which filter the pain messages on their way to your brain.

For severe pain that's linked to bodily harm, such as when you touch a hot stove, the "gate" is wide open and the messages take an express route to your brain. Nerve cells in your spinal cord also respond to these urgent warnings by triggering other parts of the nervous system into action, such as your motor nerves. Your motor nerves signal your muscles to pull your hand away from the burner. Weak pain messages, however, such as from a scratch, may be filtered or blocked out by the gate.

Within your spinal cord, the messages can also change. Other sensations may overpower and diminish the pain signals. This happens when you massage or apply pressure to the injured area. The result is that the warnings sent by your peripheral nerves are downgraded to a lower priority.

Nerve cells in your spinal cord may also release chemicals that amplify or diminish the messages, affecting the strength of the pain signal that reaches your brain.

Your brain

When pain messages reach your brain, they arrive at the thalamus, a sorting and switching station located deep inside your brain. The thalamus quickly interprets the messages as pain and forwards them simultaneously to three specialized regions of the brain: the physical sensation region (somatosensory cortex), the emotional feeling region (limbic system) and the thinking region (frontal cortex). Your awareness of pain is therefore a complex experience of sensing, feeling and thinking.

Your brain responds to pain by sending messages that promote the healing process. For instance, if you've cut your finger, it signals your autonomic nervous system, the system that controls blood flow, to send additional blood and nutrients to the injury site. It also dispatches the release of pain-suppressing chemicals and sends stop-pain messages to the injury site.

Your pain response

When pain messages reach your brain, two components determine how you respond.

Physical sensation. Pain comes in many forms: sharp, jabbing, throbbing, burning, stinging, tingling, nagging, dull and aching. Pain also varies from mild to severe. Severe pain grabs your attention more quickly and generally produces a greater physical and emotional response than mild pain. Severe pain can also incapacitate you, making it difficult or impossible to sit or stand.

The location of your pain also can affect your response to it. A headache that interferes with your ability to work or concentrate may be more bothersome — and therefore receive a stronger response — than arthritic pain in your knee or a cut to your finger.

Personal makeup. Your emotional and psychological state, memories of past pain experiences, and your upbringing and attitude also affect how you interpret pain messages and tolerate pain.

For example, a minor sensation that would barely register as pain, such as a dentist's probe, can actually produce exaggerated pain for a child who's never been to the dentist and who's heard horror stories about what it's like.

But your emotional state can also work in your favor, improving even a severe pain experience. This was illustrated by a study that compared formerly wounded war veterans with men in the general population. Men in both groups had the same kind of surgery. The combat veterans, however, required less pain medication than the others did, perhaps because they thought that the surgery was a minor matter compared with what they'd experienced in battle.

Athletes also can condition themselves to endure pain that would incapacitate others. In addition, if you were raised in a home or culture that taught you to "Grin and bear it" or to "Bite the bullet," you may experience less discomfort than people who focus on their pain or who are more prone to complain.

Acute pain and chronic pain

Acute pain is triggered by tissue damage. It's the type of pain that generally accompanies illness, injury or surgery

Acute pain may be mild and last just a moment, such as from a sting. Or it can be severe and last for weeks or months, such as from a burn, pulled muscle or broken bone.

When you have acute pain, you know exactly where it hurts. In fact, the word acute comes from the Latin word for "needle," referring to a sharp pain. A toothache from a cavity, a burning elbow from a scrape and pain from a surgical incision are examples of acute pain. In a fairly predictable period and with treatment of the underlying cause, acute pain generally fades away — when the cavity is filled, the skin grows back or the incision heals.

Chronic pain hangs on after the injury is healed. Pain is generally described as chronic when it lasts 6 months or longer. This is reflected in the word itself. Chronic comes from the Greek word for "time."

As with acute pain, chronic pain spans the full range of sensations and intensity. It can feel tingling, jolting, burning, dull or sharp. The pain may remain constant, or it can come and go, like a migraine that develops without warning.

Unlike acute pain, however, with chronic pain you may not know the reason for the pain. The original injury shows every indication of being healed, yet the pain remains — and may be even more intense.

Chronic pain can also occur without any indication of injury. Years ago, people who complained of pain that had no apparent cause were thought to be imagining the misery or trying to get attention. Doctors now know that’s not true. Chronic pain is real.

What causes chronic pain?

Frequently, the cause of chronic pain is not well understood. There may be no evidence of disease or damage to your body tissues that doctors can directly link to the pain.

Sometimes, chronic pain is due to a chronic condition, such as arthritis, which produces painful inflammation in your joints, or fibromyalgia, which causes aching in your muscles.

Occasionally, chronic pain may stem from an accident, infection or surgery that damages a peripheral or spinal nerve. This type of nerve pain that lingers after the original injury heals is called neuropathic — meaning the damaged nerve, not the original injury, is causing the pain. Neuropathic pain can also result from diseases such as diabetes or alcoholism.

Once damaged, the nerve may send pain messages that are unwarranted. For example, an increased blood sugar level associated with diabetes can damage the small nerves in your hands and feet, leaving you with a painful burning sensation in your fingers and toes.

Little is known about why injured nerves sometimes misfire and send painful messages. However, one reason is that when a nerve cell is destroyed, the severed end of the surviving fiber can sprout a tangle of unorganized nerve fibers (neuroma). This bundle of nerve tissue then starts sending spontaneous pain signals. These fibers also refuse to follow normal checks and balances that control the rest of your nervous system, keeping pain at bay.

Sensitization and pain pathways

It used to be thought that pain transmission pathways in the peripheral nerves, spinal cord and brain were hardwired circuits that simply communicated pain signals from injured or diseased parts of the body to message centers in the brain. But based on recent scientific research, there is new knowledge of how pain transmission actually works and how the conscious experience of pain is created in the brain.

One very important aspect of these new discoveries about pain has to do with a process called sensitization. An introduction to sensitization will help you to understand how your chronic pain can be so severe and why your pain may seem out of proportion to the evidence of injury or disease in the affected body tissues. Sensitization can also explain why specific treatments directed at pain relief may provide only limited benefit.

Although the neurobiology of sensitization is complex, the basic idea behind it is straightforward. When pain signals are transmitted from injured or diseased tissues, these signals can then activate (sensitize) pain circuits in the peripheral nervous system, spinal cord and brain.

The process of sensitization can be compared to the volume control on your stereo, amplifying — and sometimes distorting — the pain message. The result is a painful condition that is severe and out of proportion to the disease or original injury. Sensitization may affect all regions of your nervous system that process pain messages, including the sensing, feeling and thinking centers of your brain. When this occurs, chronic pain may be associated with emotional and psychological suffering.

A good example of sensitization is the problem of phantom limb pain. In this condition, a person can feel intense pain in the place of a missing body part, for example, an arm or a leg that has been amputated because of injury or disease. The difficult-to-treat problem of phantom limb pain is explained by persistent activation (sensitization) in the pain transmission pathways from the site of amputation up to the brain.

Scientific evidence now confirms the presence of sensitization in various pain conditions that don't involve amputation. When treatments in such cases are directed at injured or diseased tissues themselves, they have no effect on the sensitized pain pathways in the spinal cord and brain. As a result, little benefit is experienced.

Much scientific research at medical centers around the world is focused on identifying the molecular and cellular processes that cause sensitization. The results of this research are likely to provide new and better treatments for many types of chronic pain.

Research: Crasilneck HE. The use of the Crasilneck Bombardment Technique in problems of intractable organic pain. Am J Clin Hypn (UNITED STATES) Apr 1995, 37 (4) p255-66

The pain state itself is one in which internal focus is increased and motivation for change is generally high. Pain additionally produces an isolation. This can influence susceptibility. Barabasz and Barabasz (1989) studied sample of 20 patients with a variety of chronic pain syndromes. They utilized an Hypnotic technique known as Restricted Environmental Stimulation Therapy (REST). All of the patients were initially rated as having low Hypnotic susceptibility on the Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scale - (SHSS). Following exposure to the training technique, the subjects demonstrated significant increases in both SHSS scores and in pain reduction when compared to controls.

The Crasilneck Bombardment Technique consists of six diversified methods of hypnotic inductions used consecutively within one hour; the six sequential systems are typically used for 7 to 10 minutes each and include (71) relaxation, (2) displacement, (3) age regression, (4) glove anaesthesia, (5) hypnoanaesthesia, and (6) self-hypnosis. In a study conducted at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, USA, twelve consecutive patients, all of whom manifested severe organic pain problems which had not responded to any form of treatment, including stand-ard hypnosis techniques were given Crasilneck Bombardment Technique.

The results showed that ten of the twelve patients responded positively to the Bombardment Method. More interestingly, one year after the treatment, the patients estimates of pain control ranged from a minimum of 80% relief to a maximum of 90%, most of the time. The types of intractable pain treated were six head-aches, three backaches, one arthritic pain, one postherpetic neuralgia pain problem, and one temporomandibular joint pain. Crasilneck HE. The use of the Crasilneck Bombardment Technique in problems of intractable organic pain. Am J Clin Hypn (UNITED STATES) Apr 1995, 37 (4) p255-66

A meta analysis of 20 controlled studies found that patients who received hypnotherapy before or during surgery fared better than 89% of patients in control groups. Among the benefits were reduced anxiety, pain and postoperative nausea and vomiting, less blood loss, and shorter hospital stays. Anesthesia and Analgesia, June 2002.

Journal: American Journal of Hospice Palliative Care, 16(5):665-70, 1999

Hypnosis is a valuable resource for patients suffering from protracted illness to achieve a state of relaxation, to overcome insomnia, to provide pain relief, or to experience the synergism in a collaborative relationship with those who have special meaning. This article briefly reviews the general history of hypnosis and how it has emerged.

In modern times, trance work has enabled patients to create and utilize their own suggestions in order to achieve the best use of their own capacities and motivations. A more thorough understanding of trance phenomena coupled with dissociative effects, amnesias, and many kinds of sensory alterations has increased the effective spectrum of techniques available to today’s therapists.

Alden, Phyllis; Heap, Michael (1998). Hypnotic pain control: Some theoretical and practical issues. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 46 (1), 62-76.

Barabasz, Arreed F.; Barabasz, Marianne (1989). Effects of restricted environmental stimulation: Enhancement of hypnotizability for experimental and chronic pain control. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 37, 217-231.

Chen, Andrew C.; Dworkin, Samual F.; Bloomquist, Dale S. (1981). Cortical power spectrum analysis of hypnotic pain control in surgery. International Journal of Neuroscience, 13, 127-136.

Cotanch, P. H.; Harrison, M.; Roberts, J. (1987). Hypnosis as an intervention for pain control. Nursing Clinics of North America, 22 (3), 699-704

Erickson, Milton H. (1967). An introduction to the study and application of hypnosis for pain control. In Lassner, J. (Ed.), Handbook of hypnosis and psychosomatic medicine. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Evans, Frederick J. (1990). Hypnosis and pain control. Australian Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 18 (1), 21-33

Hilgard, Ernest R.; Macdonald, Hugh; Marshall, G.; Morgan, Arlene H. (1974). Anticipation of pain and of pain control under hypnosis: Heart rate and blood pressure response in cold pressor test. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 83 (5), 561-568.

Orne, Martin T. (1976). Mechanisms of hypnotic pain control. In Bonica, John J.; Albe-Fessard, D. (Ed.), Advances in pain research and therapy (pp. 716-731). New York: Raven Press.

Pollack, S. (1966). Pain control by suggestion. Journal of Oral Medicine, 21, 89-95.

Schwarz, A. (1988). Experience of pain in cancer and hypnotic pain control. Hypnos: Swedish Journal of Hypnosis in Psychotherapy and Psychosomatic Medicine, 15 (4), 195-2

|

|